Ghosts in the Grass

Posted on June 30, 2014 by bob in OffTheBeatenPath

“I don’t believe it,” the old man said. “A retriever is not a bird dog. A fine water dog, yes, but no bird dog.”

The boy shook his head in respectful disagreement, smiling at his grandfather. The old man grumbled something about self-respecting bird hunters, then turned his attention to the tea pot on the stove, steam streaming from the spout. Any moment a sharp steady note would signal the water’s readiness.

“Why don’t you use the microwave Mom bought you?” The boy gestured to the small black box which sat, unplugged, in the corner of the tiny kitchen. “It’s a lot faster.”

“Speed,” the old man said, clearing his throat for effect, “does not dictate supremacy of technique. Anticipate the song of the pot. Besides,” he paused, “that thing gives the tea an odd taste.”

He smirked, pleased with himself, and leaned back in the wooden chair. It creaked like his aged knees.

“You probably hunt birds over Labradors,” he said playfully, smiling at the boy. “I bet you shoot an auto-repeater.”

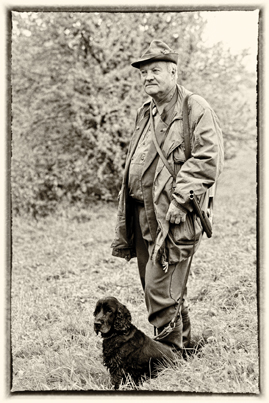

The old man loved to hunt birds more than anything, holding strong opinions on the subject. He pined after that gentleman bird of the southern woodlands, the true bird of sport. At one time it was his livelihood, raising pointers and chasing birds at every opportunity, in the company of good friends through great stands of tall pine, through cutovers, along old fencerows, pea patches and in the grass. Beggar’s lice on the wide, pine-planked floor of his home were a fact of life.

The old man especially loved a good point in the grass, where he could spread out his party around the dogs. Those riding in the wagon could see the whole production and the work of his fine canines. He loved a good covey rise where he could see each bird get up, in slow motion. He preferred hunting in the grass whether or not he toted a gun.

“Where’s the sport in simply flushing birds for a shot?” he asked his grandson. “There’s no style to it.”

More than once on that now long-gone family homestead, his pointers had locked down a point so solid you’d have sworn they were staring Medusa herself in the face. Their bodies didn’t move but for short, nearly imperceptible rhythmic breaths, years of good breeding and hours of training culminating in a perfectly orchestrated choreography of dog, bird and hunter.

“A flawless point is prettier than even the most colorful sunrise,” his grandfather would say to friends and clients after one of his dogs made an especially fine job.

It was as if the years of training in the heat, the cold, the rain, the snow, were building to that one, solid, single moment in time. The point of it all was, in the end, the point. It wasn’t for the birds; yes, the shooting was usually good over his dogs. But for the old man, it was all about the point. And a point in the grass was all the better.

That old home place wasn’t a great amount of acreage, but it was good land, soil black as coal dust, good for crops and consequently, good for bobwhites. Their ancestors had put their lives into the farm. Most who were born there, died there; the small cemetery at the crest of the hill filled with people who shared his name.

That old home place wasn’t a great amount of acreage, but it was good land, soil black as coal dust, good for crops and consequently, good for bobwhites. Their ancestors had put their lives into the farm. Most who were born there, died there; the small cemetery at the crest of the hill filled with people who shared his name.

They’d had countless hunts on the place during the old man’s life. When he was a boy, family, friends, dogs, all would load up in mule-drawn wagons, and later in trucks or ATVs. The faces in the wagons, the dogs in the brace, even the guns changed, but the birds, the birds never did. And the hunt, well, it was never anything short of magical.

“There’s nothing like a truly wild bird,” the old man had said many times, “the kind that can hide in the briars between your feet or fool your best dog with a flush a hundred yards out of range.”

He often reminisced about the hunts of yesteryear and the hunters, the dogs and the immovable points, the unexpected flushes and shots that made the outings memorable. He had met his wife on one such hunt, back when inter-family bird hunts were as common as backyard barbecues. He’d first seen her as she rode up on her own horse, alongside her family wagon. The onyx-colored mare stood out starkly against the pale sage. More beautiful than any woman he’d ever seen, he froze solid when he saw her, like one of his own dogs with a nose full of bird. His father, the boy’s great-grandfather, asked if he’d seen a ghost.

“No,” was all he could muster, but he couldn’t take his eyes off the young lady.

They were introduced later that day after she’d made an exceptional shot. She became a regular on family hunts and before long they married. She and the old man had several children, four boys then a girl, the boy’s mother.

All were “raised in the kennel” the old man would proudly say, amongst the very dogs which were his livelihood and greatest passion. She’d been dead several years and their children had departed, like a morning fog in the warming sun, slowly and imperceptibly dissipating until no fog remains. In the silence, the boy sensed a growing chasm between himself and the old man and he tried to close the distance.

“Gramps, tell me about all the wild covey-hunting you did when you were my age,” he said, expecting the request to lighten the mood and get their visit back on track. The old man smiled a half smile and looked down at the rug.

For some time, no wild birds had existed in hunt-able numbers. The culprits were many. Changes in farming, the explosion of deer hunting and the land management practice paradigm shifts it had brought, even the price of fur. It was a subject dear to the old man’s heart and one that usually got him to talking during one of these visits. There were still coveys here or there, but you couldn’t hunt them right, he would say. Coyotes were another culprit, and they had spread, near as quickly and just as devastating as fire ants.

The friends had disappeared too, as had the dogs. Not all at once, but rather slowly, scattered like a wild covey. With fewer friends to hunt with he didn’t need such a large brace of dogs.

With fewer dogs he couldn’t take as many friends afield. Though times and circumstances changed, the old man’s zeal for the birds remained, at least until his last dog died.

He never told anyone how much it tore at him inside, like the death of close family, because he knew that as he dug that shallow grave he was in fact burying a part of himself. After that last dog he never hunted again. He blamed it on his knees, his unsteadiness, his failing eyesight – that he was a danger, a liability to others – but the truth was he couldn’t bring himself to go.

“Gramps,” the boy said, “you feeling OK?”

“I’m fine,” the old man said, letting a half-smile creep across his face. “I was just thinking about your grandmother. She was one hell of a shot, you know.”

“I remember,” the boy said, lying. If it made the old man feel better to remember it that way, it was better for them both for him just to shake his head and agree.

The old man sank a little deeper in his chair, and the boy could tell he was slipping off to that melancholy place he went sometimes when talk turned to dogs and birds and times gone by.

The boy knew nothing of that place, except that the old man went there from time to time. From the deep distance in his grandfather’s eyes, the boy could tell that ghosts walked there, in the grass.

Niko Corley spends his free time on the water or in the woods, and earned his charter boat license in 2012. He can be contacted at cootfootoutfitters@gmail.com.