History’s Stage

Posted on October 3, 2012 by bob in Features

by Willie Moseley; photos courtesy Payne Lee Architects; Bob Corley

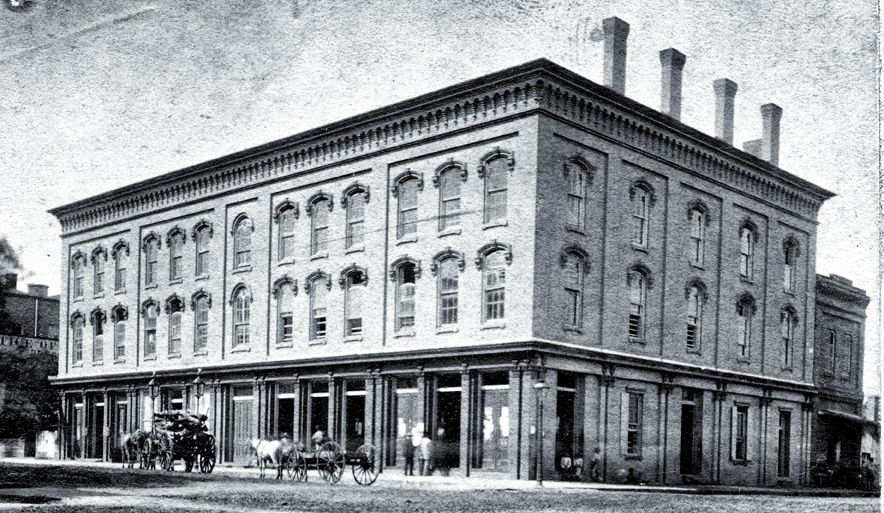

By the beginning of the 1960s, downtown Montgomery was in a downward spiral regarding retail business. Suburban shopping centers such as Normandale and Eastbrook were inexorably siphoning off customers to closer and more-modern stores…and those new shopping centers also offered gigantic parking lots. Nevertheless, some downtown stores, particularly clothiers, would press on. Such determined—or stubborn—retailers included Webber’s, located at the corner of North Perry Street and Monroe Street, across from City Hall.

And one might wonder if young Baby Boomers whose parents still took them downtown to shop for clothes might have glanced upwards when they were standing outside of Webber’s, noting that the building housing the clothing store was actually three stories, and that the top two stories were built of brick in a definitive and attractive architectural style (Webber’s was framed in aluminum siding).

Moreover, those Boomers—through the balance of their lives—may not have been aware that the building once housed the Montgomery Theatre, which was a focal point for numerous historical events as well as local entertainment during its existence of less than a half-century.

Commissioned by railroad magnate Charles Pollard and designed by architect Daniel Cram, the Montgomery Theatre was completed in 1860, having been built in a modified “Italianate” style, which was popular in the U.S. in the 19th Century (Cram’s residence, the Lakin House, was also an Italianate design, and is located in Old Town Alabama in downtown Montgomery). Exemplary of the style were the ornate window frames, which had decorations in the top center that appeared to be carved, but were cast iron.

The Perry Street side had not only the entrance to the theatre, but several ground floor shops including a post office and a bar. The theatre itself was accessed by walking up a grand staircase to a perimeter walkway to access the appropriate level—the orchestra level could be reached by a few downward steps, while another staircase led to upper levels.

Two balconies were originally built, and were comprised of a complete horseshoe known as the Dress Circle, and a tiny second balcony that had two segregated sections—one for blacks, and one for prostitutes from nearby brothels. Later, the seating capacity was increased when the second balcony also became a complete horseshoe.

The ceiling of the theatre was very ornate, featuring 75-foot beam spans and a chandelier. The stage was originally lit by kerosene lamps with reflectors. Later, gas lighting, then electrical lighting would be added to the facility. A basement housed theatrical props and supplies.

The storm clouds of secession and war were gathering when the Montgomery Theatre opened in the fall of 1860, and some of its most historical events occurred during the first year of its existence.

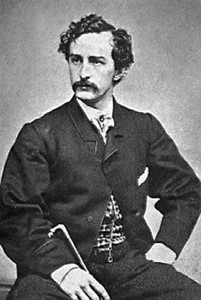

One of Booth’s roles on the Montgomery Theatre stage was Shakespeare’s Richard III, a despotic ruler who is eventually overthrown and murdered.

John Wilkes Booth, a member of one of America’s most celebrated acting families, was slated to perform at the grand opening, but was unable to do so, according to Col. Bob Bonn. Bonn, along with fellow Montgomery historian Mary Ann Neeley, has written extensively about the Montgomery Theatre.

“He was invited and booked for the theater’s first opening, but had wounded himself in Columbus, Georgia, at his prior engagement,” said Bonn. “He was on a theatrical tour of the South, and witnessed all the excitement of secession rallies in Montgomery. His injury involved a pistol or a knife, and probably lots of alcohol and carousing with a friend. The accounts are vaguely worded; in any event, he was in no physical shape to perform any action plays by Shakespeare.”

But Booth did follow through with his Montgomery obligation some days later, performing there several times through early November.

“He did excerpts from Richard III, Hamlet, and Julius Caesar, and two period pieces on that first night,” said Neeley. “He was traveling under the name of John Wilkes, because he didn’t want to depend entirely on his family’s name; he wanted to make it on his own.”

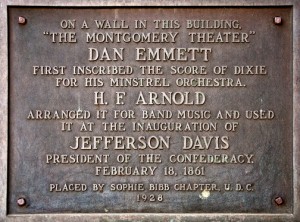

Another historic occasion in the early months of the theater was a performance by Bryant’s Minstrels, a northern entertainment troupe led by Dan Emmett. One tune the group performed,

“Dixie’s Land,” had been written by Emmett in Ohio in 1859. The upbeat song impressed Herman Arnold, the leader of the Montgomery Brass Band, who conversed with Emmett, and wrote the music and lyrics in charcoal on a backstage wall, later transcribing them for his own band.

The song would become known as “Dixie,” and be played during the celebration of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis, elected President of the Confederate States of America following the secession.

Secession also figured into the early days of the Montgomery Theatre, as orators such as William Lowndes Yancey and future C.S.A. Vice-President Alexander Stephens took to the stage in front of huge crowds to advocate separation from the United States.

During the Civil War, traveling actors and musicians did not perform at the theater, but local entertainers utilized the venue, which was ultimately closed. Pollard re-opened the theater in September of 1865, but it witnessed some hostile confrontations between occupying Union troops and local citizens. In 1875, the Montgomery Theatre was the scene of what may have been the first attempt at desegregation in the Deep South, preceding the action of Rose Parks onboard a city bus by eight decades.

The Civil Rights Law of 1875 had mandated desegregation of public facilities. It would be disallowed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1883, but the year the law was passed, several prominent blacks tried to integrate the “Dress Circle”. Though historically significant, the confrontation was ultimately unsuccessful.

The Montgomery Theatre would succumb to entertainment trends in the early 20th Century, closing in 1907.

“Vaudeville killed it when a large theatre was built across from where the Davis Theatre is presently located,” said Bonn.

The neglected interior of crumbling plaster, exposed wiring and brick, and rusting metal, offers few hints of the former glory of this once proud structure.

The building ultimately became a department store, with the upper stories used for storage. Some images still remain on the walls where structural elements of the theater’s interior were installed, as do scraps of wallpaper in certain areas.

But the building at the corner of North Perry and Monroe may ultimately become a part of the present-day renaissance of downtown Montgomery. It is owned by the Riverfront Development Authority, but a purchase agreement for its sale to an architectural and construction company is pending as of this writing. The renovated interior will house apartments, office space, and food venues, and tenants are already being lined up.

“It’s still ‘hanging in the wind’ a bit,” said Neeley, “but everybody’s very upbeat about it.”

A rendering of a restaurant interior by Payne Lee Architects provides a glimpse of what may be in store when the building undergoes its 21st century transformation.

Bonn also advocated the preservation of the building.

“The Montgomery Theatre has a grand history,” Bonn said. “It saw much in its forty-seven year operational history. The fact that it has survived at all is a miracle!”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] opening, but “had wounded himself in Columbus, Georgia, at his prior engagement,” according to Col. Bob Bonn who has written extensively about the Montgomery Theatre. However, he did perform some days later, […]