“Bear” Bryant Remembered

Posted on September 2, 2013 by bob in Features

by Tom Ensey. Photos by Bob Corley, and contributed by the Bryant Museum, U. of Alabama.

Paul “Bear” Bryant would have been 100 years old this month. Dead more than 30 years, ‘Bama fans still talk as if he were alive. He remains the standard by which college football coaches are measured, and like all who become legends, the man he was has faded, replaced by the myth. And myths don’t die.

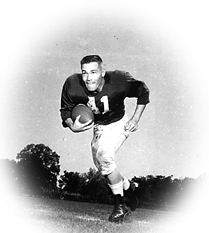

Marlin “Scooter” Dyess was a sophomore in 1958 when Bryant returned to his alma mater to take over a program that had won four games in three years. Alabama’s new coach came from Texas A&M, where in 1954 he put the team through brutal practices with no water breaks in a blasted landscape near Junction, Texas. The 35 survivors became known as “The Junction Boys.” One of those Junction Boys was Gene Stallings, who became an assistant coach under Bryant and later Alabama’s head coach.

“Coach Stallings told me we did the same things they did, only we lived in dorms and they lived in quonset huts,” Dyess said. “It was like going from dark to daylight from where we had been.”

To everyone’s surprise, Alabama went 5-4-1 that first year.

“We didn’t know we weren’t any good,” said Dyess. “I wasn’t the most talented player, but I did the best I could with what I had.” That’s the kind of guys who played on those first two teams, he said.

Dyess’ biggest athletic honor was being selected captain for the first of Bryant’s 24 bowl games at Alabama, the Liberty Bowl in Memphis. After moving to Montgomery to start a successful business, they stayed in touch until Bryant died. He still recalls the coach’s soft side.

Dyess had a friend with a special-needs child who wanted an autographed picture of Coach Bryant for Christmas. Bryant went by the house and delivered it in person. If former players had problems with money, drugs or alcohol, Bryant started a fund to help them out. If they could pay it back, they did, and if they couldn’t that was all right, too.

“I loved the guy,” Dyess said. “A lot of players didn’t. We all respected him.”

Tom Somerville arrived as a freshman in 1964, a national championship season. He played on the 1965 team that won the national title with a 9-1-1 record after two teams ahead of them in the polls lost and ‘Bama shocked Nebraska 39-28 in the Orange Bowl.

“They had big, old guys, and they had black players. It was the first time most of us had played against black players,” Somerville said. “Coach Bryant told us to be sportsmanlike. If we knocked one of them down, help him up and pat him on the back. We looked like ants after we tackled them,” he said, laughing. “We all ran over and swarmed them to pat them on the back.”

And while Alabama’s players were usually smaller than the teams they played, they weren’t that much smaller. Somerville said he stood 5-foot-9 and weighed about 195 pounds. But he was listed in the program at 178, which was accurate, sort of.

“Coach Frank Howard at Clemson accused Coach Bryant of fudging the weights in the program,” he said. “So, Coach Bryant decided he was going to have them notarized.”

After a brutal afternoon practice during preseason two-a-days, the players weighed and a notary public certified them.

“I weighed 178 then, but that morning I was probably 15 pounds heavier,” Somerville said. “That was my weight in the program for the rest of my career.”

Phillip Marshall was sports editor of the Montgomery Advertiser from 1980 to 1991. He covered Bryant’s career before that as a sports editor at the Decatur Daily and Birmingham Post-Herald. His father, Benny Marshall, was a close Bryant friend.

“My first memory of him, my brother and I went to a press conference with my dad,” Marshall said. “We were playing outside of Bryant Hall. Once the press conference started, Coach Bryant asked my dad if that was his kids, and dad told him yes. So he stopped the press conference, came out and told us hello, then went back in.

“Some guys were intimidated by him, but I guess he had a soft spot for me,” Marshall said.

Bryant wasn’t an innovator, said Marshall, but he was a brilliant adapter. He didn’t invent the wishbone offense, but ran it better than anybody else and incorporated passing into it. Marshall was there for Bryant’s transition from little, quick teams to bigger, quick teams.

“I asked him one time if he could still win with those little, quick guys, and he had that cigarette in his hand and he said, ‘Phillip, a big fast one will whip a little fast one every time.’

“He was a master of getting guys to play near the top of their ability,” Marshall said. “But he had a lot of really good players, too.”

Bryant's first coaching staff at the U. of Alabama. On the back row, in a white hat, is future 'Bama head coach Gene Stallings.

Marshall said Bryant dealt him one of his most embarrassing moments at a press conference before Alabama resumed a series with Georgia Tech after a long hiatus. The series had gotten bitter, and prior to a game at Tech’s home field, Bryant wore a helmet onto the field in case the fans threw something at him.

“I asked the first question at the press conference, and I said, ‘Coach, are you going to wear a helmet on the field before this game?’”

Bryant stared at him a minute, then shot back.

“I raised you,” Bryant said to Marshall. “I used to drink coffee with your daddy when it was a nickel a cup. Is that the best question you could come up with?”

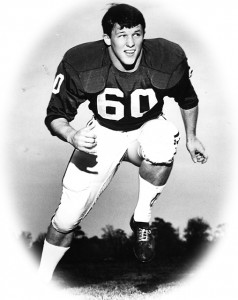

Mike “The Hook” Raines and his brother Pat, grew up Auburn fans and starred at Sidney Lanier High School. They were recruited by both Alabama and Auburn. Mike said he knew he was going to play wherever his brother played, because of his dad, who never missed either of their games.

Raines was a freshman in 1970, the year Southern California came to Birmingham and crushed the Crimson Tide 42-21 in the season opener. The Trojans, coached by Bryant friend John McKay, had an all-black offensive backfield.

“They had 6-4, 265 offensive linemen who were as fast as we were,” Raines said. “We had a guy, Terry Rowell, who weighed 195 at defensive tackle. We got hammered.”

The next year, Alabama started recruiting black players.

Bryant also made a dramatic switch to the wishbone offense, which he installed in the three weeks of preseason practice before the opener against USC in Los Angeles.

“The first day of practice, Coach Bryant told us we were going to sink or swim with the wishbone,” Raines said. “He put up blankets around the practice field. You could have seen in if you had a helicopter, but not otherwise. We went to Southern Cal as 19-point underdogs and beat them.”

There’s no way that would have been possible now, Raines said. One ‘tweet’ would have blown the whole cover.

“The reason we won football games was because we worked harder in the off season, and we were better prepared,” said Raines. When you went out on Saturday, you didn’t have to think what your assignment was. If you take care of your responsibility, and take care of what you have to do, after about 1,000 repetitions, you win games.”

Raines was part of a second turnaround at Alabama – following three mediocre seasons, then launching into a hyper successful era.

“It was an evolution into a new age,” he said. “Most coaches wouldn’t have taken the risk. He showed a lot of forward thinking. We played with two or three sets of running backs, ran the triple option, threw it at them all day long. We won a lot of football games.”